The Métis Nation is comprised of descendants of people born of relations between First Nations women and European men. The offspring of these unions were of mixed ancestry. Over time a new Indigenous people called the Métis resulted from the subsequent intermarriage of these individuals. This “ethnogenesis” of distinct Métis communities along the waterways and around the Great Lakes region of present day Ontario occurred as these new people were no longer seen as extensions of their maternal (First Nations) or paternal (European) relations, and began to identify as a separate group.

Distinct Métis settlements emerged as an outgrowth of the fur trade, along freighting waterways and watersheds. In Ontario, these settlements were part of larger regional communities, interconnected by the highly mobile lifestyle of the Métis, the fur trade network, seasonal rounds, extensive kinship connections and a shared collective history and identity.

Métis citizens are represented at the local level through MNO Chartered Community Councils. The Councils are the foundation of the MNO in its push toward self-government and foster community empowerment and development for Metis citizens living within their geographic territory.

The horizontal figure or infinity symbol featured on the Métis flag was originally carried by French ‘half-breeds’ with pride. The symbol, which represents the immortality of the nation, in the centre of a blue field represents the joining of two cultures. Though the historical origins of the infinity flag continue to be a source of debate there is no doubt that the Métis flag is carried today as a symbol of continuity and pride.

One of the most prominent symbol of the Métis Nation is the brightly coloured, woven sash. In the days of the voyageur, the sash was both a colourful and festive item of clothing and an important tool worn by the hardy tradesmen. Doubling as a rope when needed, the sash served as a key holder, first aid kit, washcloth, towel, and as an emergency bridle and saddle blanket. Its fringed ends could become a sewing kit when the Métis were on the land. The art of sash weaving was brought to the western regions of Canada by Voyageurs who encountered the bright ‘scarves’ through contact with French Canadians.

The finger-weaving technique used to make the sash was firmly established in Eastern Woodland Indian Traditions. The technique created tumplines, garters and other useful household articles and items of clothing. Plant fibres were used prior to the introduction of wool. Europeans introduced wool and the sash, as an article of clothing, to the Eastern Woodland peoples. The Six Nations Confederacy, Potawatomi, and other Indian nations in the area blended the two traditions to produce the finger-woven sash.

The French settlers of Québec created the Assumption variation of the woven sash. Sashes were a popular trade item manufactured in a cottage industry in the village of L’Assomption, Québec. The Québécois and the Métis of Western Canada were their biggest customers. Local Métis artisans also made sashes. Sashes of Indian or Métis manufacture tended to be of a softer and looser weave, and beads were frequently incorporated into the design.

The Métis share the sash with two other groups who also claim it as a symbol of nationhood and cultural distinction. It was worn by eastern woodland Indians as a sign of office in the 19th century, and French Canadians wore it during the Lower Canada Rebellion in 1837. It is still considered to be an important part of traditional dress for both these groups. The sash has acquired new significance in the 20th century, now symbolizing pride and identification for Métis people. Manitoba and Saskatchewan have both created “The Order of the Sash” which is bestowed upon members of the Métis

The fiddle has figured prominently in the lifestyle of the Métis people for hundreds of years. It is the primary instrument for accompanying the Métis jig. The famous ‘Red River Jig’ has become the centrepiece of Métis music. Since this European instrument was exceedingly expensive in early Canada, especially for grassroots Métis communities, many craftsmen learned how to make their own. The fiddle is still in use today and plays a prominent role in celebrations as a symbol of our early beginnings and the joyful spirit in which we lived and grew. Fiddle and jigging contests are always popular events and provide an opportunity to showcase the fiddle as a symbol of Métis nationhood and pride.

The Red River Jig, the unique dance developed by the Métis people, combines the intricate footwork of Native dancing with the instruments and form of European music. Often the Métis made their own fiddles out of available materials because they could not afford the European imports. Traditionally, dancing started early in the evening and would last until dawn. Witnesses were often dumbfounded by the energy and vitality evident during celebrations which was matched only by the long, arduous days of labour necessary to keep Métis communities running. Métis people continue to enjoy jigging, and have local, provincial and national dance teams who attend conferences, exhibitions and powwows.

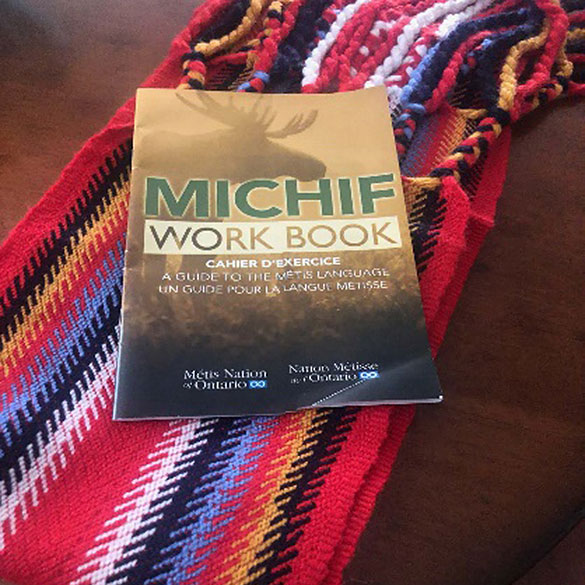

The Métis are a distinct Aboriginal people with a unique history, culture and territory that includes the waterways of Ontario, surrounds the Great Lakes and spans what was known as the historic Northwest. The citizens are descendants of people born of relations between Indian women and European men who developed a combination of distinct languages that resulted in a new Métis specific language called Michif. In Ontario, Michif is a mixture of old European and old First Nation languages and is still spoken today by some in the Métis community. Efforts are underway to rescue and preserve this critical component of Métis culture.